Interview

Ruoyu Gong

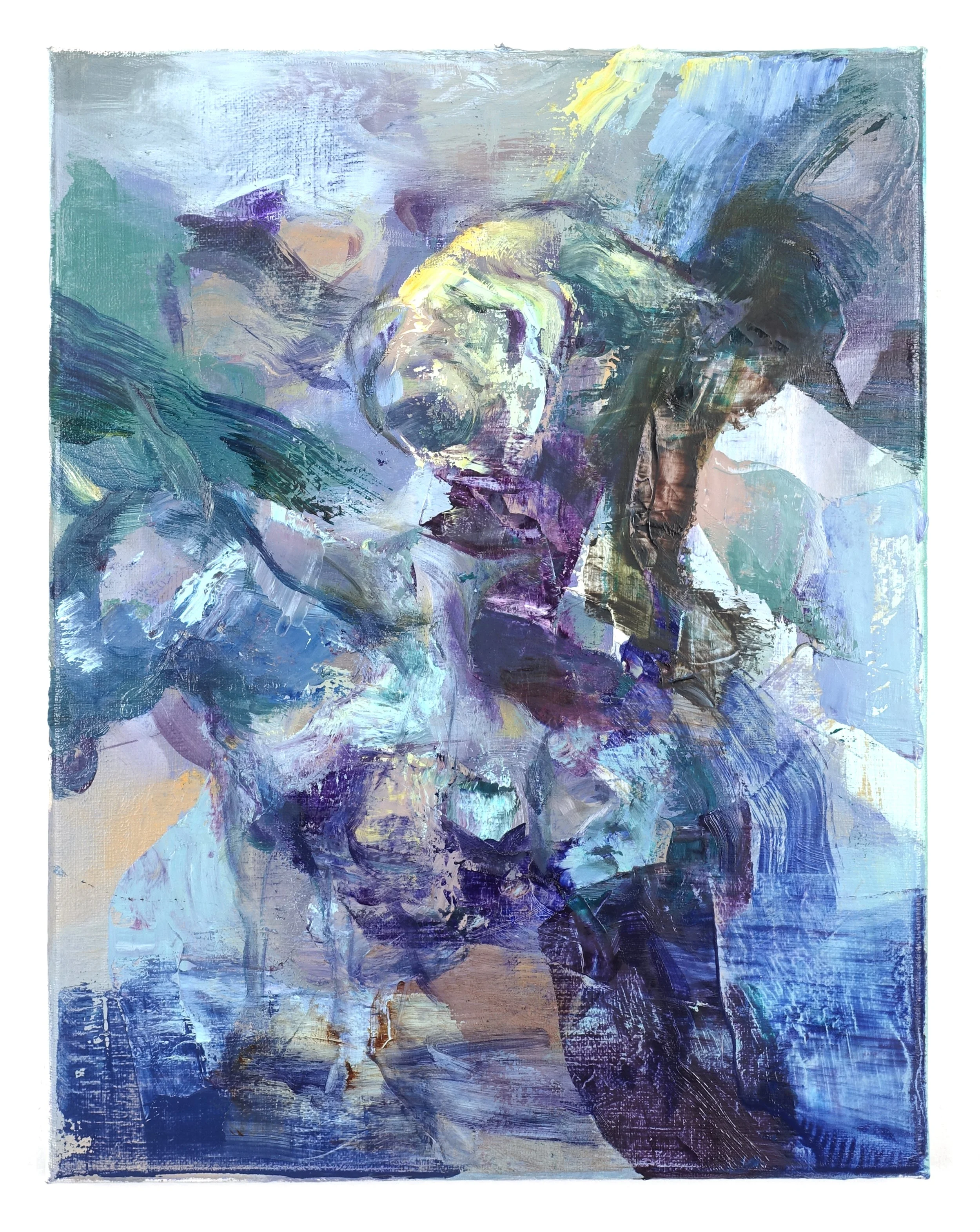

Ruoyu Gong (b. 1999, Beijing, China) is a New York based artist whose practice centers on painting while extending across bas relief sculpture, monotype, collage. In the past year, his work has revolved around the recurring image of the donkey — a motif rooted in the cultural metaphor of the traditional Chinese crosstalk (xiangsheng) piece The Bell Score and, more profoundly, a projection of the artist’s own identity, emotional tension, and cross-cultural negotiation. In Gong’s paintings, the donkey has shifted from a recognizable, expressive figure to increasingly abstracted forms: from howling mouths and contorted bodies to tangled lines and fractured symbols. It has become a visual language through which he examines humor, vulnerability, cultural awareness, and self-mockery. After extensive experimentation with mixed media, Gong has returned to the core discipline of oil painting. He now seeks to merge the spontaneity, accident, and disruption cultivated through monotype and collage with the material weight, tactility, and painterly depth of oil.

His current practice emphasizes bodily engagement, rhythmic brushwork, and a heightened sense of formal structure and tension — a constant negotiation between intuition and control, chaos and order, striving toward what he describes as “a calibrated state of productive ambiguity.” Gong’s work is informed by both Eastern and Western art histories. His early fascination with Western old masters such as Caravaggio and Rubens was rooted in their dramatic use of light and vivid depiction of the human form, while German contemporary painters like Gerhard Richter and Neo Rauch have profoundly shaped his understanding of psychological depth, historical awareness, and the complexity of painterly language. At the same time, Chinese aesthetics, particularly the poetics of restraint, ambiguity, and the importance of what remains unsaid, continue to anchor his sensibilities. The conceptual clarity of Xu Bing, the abstract distillation of Tan Ping, and the narrative expressive power of Jia Aili all contribute to the cultural matrix that nourishes his practice. Navigating a cross-cultural life, Gong perceives Chinese introspection and Western expressive freedom not as contradictions but as two forces in constant dialogue — sometimes in tension, often mutually generative. The donkey in his paintings emerges from this negotiation: a cultural archetype and a personal avatar, at once the laboring beast and the one holding the whip, embodying the psychological oscillation between discipline, exhaustion, rebellion, and humor.

In 2025, Gong earned his MFA in Painting at the New York Academy of Art, where he received the Patron’s Scholar Award. He earned BFA in Illustration with honors from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2023. His work has been exhibited in New York, Milan, London, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, and he has received numerous honors including First Prize in the YICCA International Contest of Contemporary Art, the Emerging Artist Award from The 5th Youth in the New Era, and First Place in the Mirrors and Masks International Juried Exhibition. His practice and interviews have been featured in publications such as Harper’s Bazaar Art, Robb Report, Art China, Art Review, Artist Talk Magazine, and Divide Magazine.

What is your background and how did you start your journey in the art world?

“I started drawing when I was really young, probably in elementary school. Back then, I got into the habit of drawing little figures, kind of like children’s illustrations. Whenever I had a piece of paper and some pens, I would just start drawing characters I liked. At the time, I was really into comic books. My parents noticed how much I enjoyed drawing, so they sent me to a youth art program in Beijing, China—something similar to a community art school. I mainly studied figure drawing there. After a few years, I was formally sent to study with an academy-trained instructor, where I began learning professional drawing skills like sketching and color theory. I started this more formal art training around the age of ten and continued until I was fourteen.

After that, I moved to the U.S. and attended an art high school, which was when I really entered a structured art education system. After high school, I went on to study art in college in Rhode Island, and then continued with art in graduate school in New York. Since graduating, I’ve been focusing on my own studio practice. Altogether, I’ve spent over a decade in continuous, professional art training and making work.”

What inspires you?

“I think I’m inspired by many different forms of art. I grew up in Beijing, China, and from a very young age I was deeply drawn to a traditional Chinese performance art called xiangsheng. It’s a form of comedy where two performers talk on stage and create humor through dialogue. It’s very traditional, but it has also become popular again in recent years. Because I grew up with this kind of comedy, I often play xiangsheng recordings in the background while I’m working. A lot of the material is already very familiar to me, but it functions almost like a source of comfort. Having it playing makes me feel connected to my hometown. Many of its plots and narrative structures gradually find their way into my work, especially influencing the more absurd or grotesque elements in my paintings.

Film is another important influence. I’m especially drawn to the work of Chinese director Jiang Wen. The dark humor in his films feels like an extension of traditional Chinese humor to me, particularly in the way jokes are constructed and how language is used. At the same time, personal memories and lived experiences also enter my work, but they’re usually filtered through these theatrical and comedic influences. Because of that, the work doesn’t read as a straightforward personal history. Instead, it becomes something newly formed—an interwoven mix of different inspirations layered together.”

What themes do you pursue? Is there an underlying message in your work?

“If I had to sum up the themes in my work with a single phrase, I’d say it’s about facing the frustrations of everyday life with a sense of self-mockery. My practice is still primarily painting, but in recent years I’ve been working on a larger scale. As the paintings get bigger, they can hold more elements, and the narratives become more layered and complex. That kind of structure feels very natural to me—it allows the work to grow organically without forcing the subject matter into a fixed direction. Because of that, my paintings often include absurd or slightly grotesque interactions between figures.

Visually, the work sits somewhere between abstraction and figuration. Sometimes I exaggerate the proportions of a figure; other times, parts of a body dissolve directly into the background. I also like breaking and reorganizing spatial relationships—blurring the foreground while rendering the background more solid, creating a sense of spatial dislocation. As for an underlying message, it’s hard to reduce it to a single statement. More than anything, my approach is about honestly reflecting my own lived experiences. I’m especially interested in the absurdity of everyday life, and I try to extract that feeling and translate it into a painterly language. Even though the work comes from a very personal place, I hope viewers can connect to it through the medium of oil painting. I don’t want to be didactic, but I believe that creating this kind of connection is meaningful in itself. It’s closer to a sense of awareness—recognizing the absurdity in life can sometimes make it easier to face reality. On a formal level, I want my paintings to offer layered, open-ended narratives that invite viewers to spend more time with them. Ideally, each encounter reveals something new, rather than the image being fully ‘read’ all at once and then exhausted.”

How would you describe your work?

“I’d say my work has gone through a significant transformation. From when I first started learning oil painting to where I am now in my own practice, that shift is closely tied to the past decade of traditional, academic realist training I received. For a long time, I placed a lot of importance on craftsmanship. I believe that in any artistic discipline, technical skill really matters—you need a strong enough foundation to carry what you want to express. Because of that, I’ve always been very focused on improving my technique, constantly wanting to sharpen my knife. At this stage, though, I’ve started to intentionally loosen—and sometimes abandon—some of the rules and discipline that once defined my technique. Not because technique isn’t important, but because I’ve realized it can sometimes lead to a kind of self-indulgence, where skill itself starts to limit what I actually want to say. When that happens, I change my working method. I let the painting begin in a more unrestricted way, allowing it to grow freely. Technique comes later, as a tool that serves the work rather than something that confines it.

Most of my paintings now are based on imagination. I rarely use photo references, and I don’t really paint directly from observation. Figures often emerge through the process itself, and sometimes a figure will gradually transform into something else as I work. I choose to trust my instincts, even knowing that some of these elements may eventually be covered or erased. Methodologically, my work is a constant collision between intuition and reason. In the beginning, I try to remove as much rational control as possible—I don’t want to think too early about correct perspective or ideal proportions, because that tends to restrict intuitive movement. After that first intuitive phase, I’ll start looking for structure within the disorder, trying to establish some sense of order. But if that order doesn’t truly hold, if the painting starts to feel rigid or forced, I’ll break it again by returning to intuition. That involves a lot of covering, sanding, smearing, and scraping. In the end, the painting becomes the result of an ongoing struggle and entanglement between intuition and reason, eventually arriving at a fragile but necessary balance.”

Which artists influence you most?

“When I was younger—especially from high school through college, over those five or six years—the biggest influence on me was Western classical masters. Artists like Michelangelo, Caravaggio, and Rubens were hugely important to me, so for nearly a decade I was really focused on refining my technical skills. That was true when I was studying in China, and it continued through my college years. I was especially drawn to how classical oil painting handles light and shadow, and the way figures feel so vivid and alive, almost like they’re about to step out of the painting. That made me feel that oil painting is an incredibly versatile medium, something that can hold a lot of complexity and depth. As I moved further into college and started studying more art history and theory, my interests gradually shifted toward modern and contemporary art.

Now, I’m especially drawn to abstract expressionism and broader forms of expressionist painting. These artists often build on Western realist traditions but combine them with more expressive, subjective languages, creating something very personal. Some artists who really inspire me now include Neil Rauch, Willem de Kooning, Cecily Brown, Rupert Kaufman, and Anselm Kiefer. In my own practice, I feel like my path runs parallel to art history in a way. I come from an academic, traditional background, but now I’m interested in using the techniques and knowledge I’ve learned as tools for my own personal expression.”

What is your creative process like?

“I usually begin my paintings on unstretched canvas. I lay the canvas directly on the floor and start with a very diluted layer of acrylic paint. This first layer is completely abstract—different colors bleed into each other, creating a transparent, fluid surface. Once that layer dries, I start working on top of it with oil paint, searching for forms and gradually covering areas. As I keep painting, more recognizable images begin to emerge, and that’s when I start focusing on the interactions and gestures between figures. After that, I often leave the painting alone for a while. When I return to it later, I can see more clearly what no longer feels right. At that point, I’ll rework the painting—sometimes by covering areas with thicker paint, sometimes by sanding things down, and sometimes by placing the canvas back on the floor and adding another layer before painting again. Through this process, traces of earlier stages are often preserved and remain visible in the final work.

After going back and forth like this—building, erasing, and rebuilding—the painting may suddenly arrive at a state that feels resolved to me. But sometimes it doesn’t. Failure is always a possibility. For me, the act of making a painting is really about negotiating with uncertainty, or even learning how to embrace that uncertainty and the probability of failure.”

What is an artist’s role in society and how do you see that evolving?

“I think an artist’s role in society begins with the ability to observe the world honestly, and to reflect on those observations with the same level of sincerity. During the creative process, it’s easy to be pulled in by external forces—whether that’s commercial pressure or more surface-level desires, like wanting to be seen, recognized, or validated. These influences can distort artistic expression, making observation feel narrower, weaker, or more superficial. For me, being an artist requires the courage to look at the world truthfully, and to translate what you observe and experience into an artistic language with honesty and openness. This process is full of challenges and uncertainty. What you observe isn’t always beautiful, and the act of translation doesn’t always succeed. That uncertainty is part of why the artistic path is so difficult. I also think the identity of the artist is changing.

Today, artists are increasingly expected to become more well-rounded, drawing not only on artistic skills but also on knowledge and abilities beyond art itself. The world has become more interconnected, and different fields now overlap and influence one another rather than remaining isolated. Art is especially affected by this shift. Beyond technical training and studio practice, artists need to stay sensitive and curious about other disciplines, continuing to learn and expand their perspectives. I think the future will move even further in this direction—toward a more interdisciplinary and cross-field way of thinking and working.”

Have you had any noteworthy exhibitions you'd like to share?

“I recently saw an exhibition in Chelsea that I thought was incredibly strong—it was a solo show by Jennifer Packer, who is a painting professor at RISD, featuring mostly her more recent work from the past couple of decades. I’ve always really admired her paintings. She works in a kind of expressionistic figurative language. The exhibition included many large-scale works. She uses a lot of transparent paint with very intense, bright colors, along with highly lyrical linework to construct her figures. Her subjects are African American individuals, whom she invites into her studio and paints through close observation. I felt that her newer works carry even more power than before. Some of the paintings are nearly wall-sized, and when you encounter them in person, the material presence becomes extremely intense. The transparency of the paint layers, combined with scraping and smearing, creates a physical and sensory impact that feels overwhelming in the best way. Interestingly, her smaller works feel more restrained and precise, while the large-scale paintings are much more expansive and bold. That contrast—between control and openness, restraint and force—creates a strong sense of drama throughout the exhibition. Her handling of material plays a huge role in making the show feel so satisfying to experience. Seeing this exhibition also influenced my own practice, especially in thinking about how to loosen up more in large-scale work and allow that sense of bold, sweeping movement to come through more clearly.”

Website: www.ruoyugong.com

Instagram: @ruoyugong_fineart