Interview

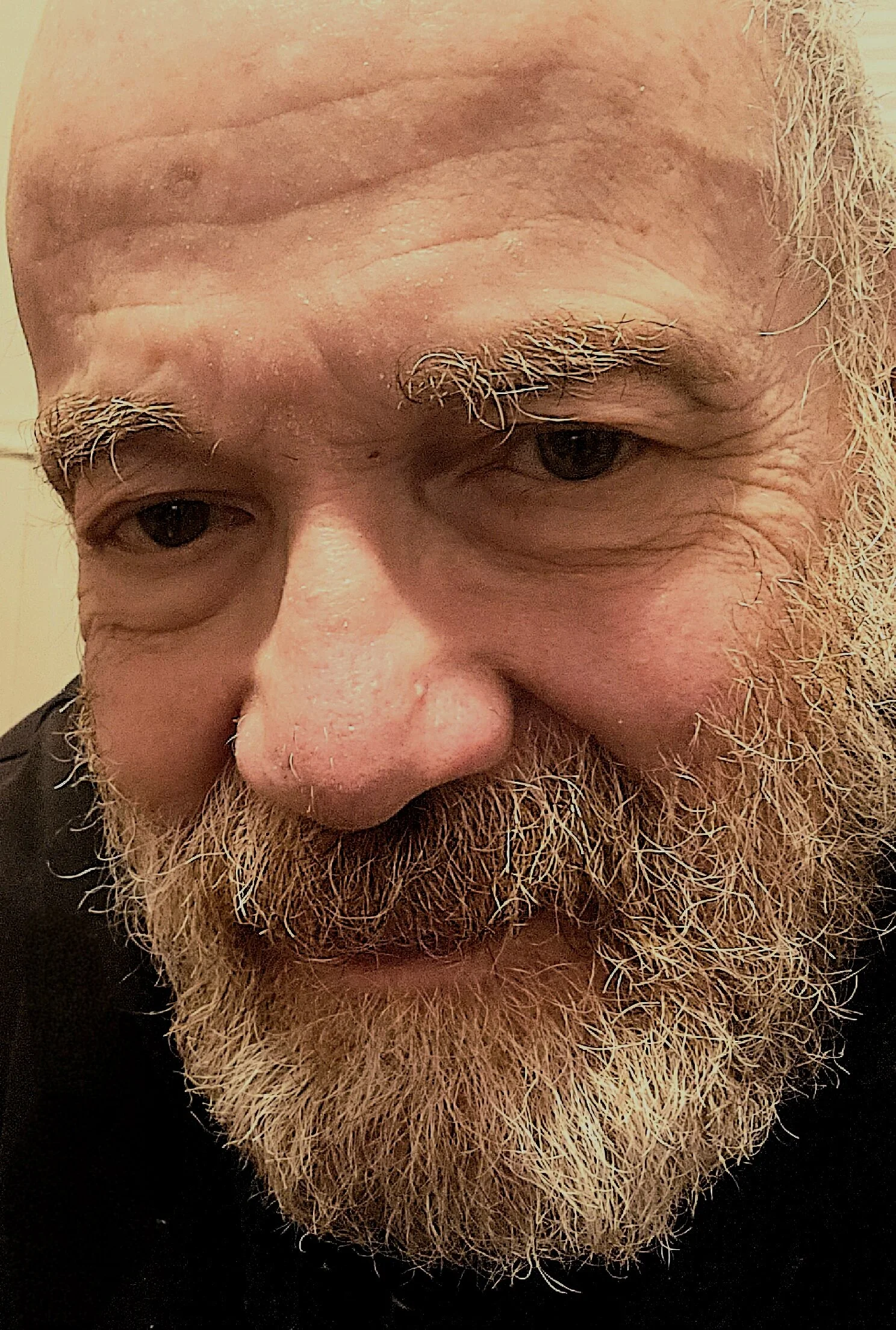

Tony Brinkley

Tony Brinkley's poetry, art and translations have appeared in the Mississippi Review, Another Chicago Magazine, Beloit Poetry Journal, Cerise Press, Drunken Boat, Four Centuries, Hungarian Review, and many more. Before retirement, Brinkley taught literature at the university of Maine. He is co-editor (with Keith Hanley) of Romantic Revisions (Cambridge University Press).

What is your background and how did you start your journey in the art world?

“After I retired (I taught literature at the University of Maine) and in response to the pervasive violence from which I have been largely protected, I began to make poems without words - icons - because I didn't know what to say. When icons become poems without words, gazing complements reading. Reading begins with looking and noticing. These icons began with moments of pareidolia, of seeing imaginary things that I could find in the photographs I have been obsessively taking (without knowing it, I was adopting an approach that Leonardo da Vinci recommends for painters: ‘Look attentively at old and smeared walls, or stones and veined marble of various colours; you may fancy that you see . . . heads of men, various animals, battles, rocky scenes, seas, clouds, woods… It is like listening to the sound of bells, in whose peeling you can find every name and word that you can imagine’). Starting with photographs of the things around me - in the house, in the yard, on the street, in the garden. I began to see what my phone could picture; as I looked at the phone's tiny screen, as I edited the photography with the limited editing - rearrangements and montage for which the phone allowed - I found images I hadn't seen before but (like the animals that surface from the face of clouds or the rock walls in paleolithic caves) were beginning to come to life. I began to see what my mind was ready (but unprepared) to witness: poems without words, icons that faced me - looking for words. When I listened, their voices were shadows (sometimes hungry ghosts or good dybbuks) that like an inaudible murmur of bells I might almost overhear.”

What inspires you?

“As I have aged (I am 77), I have come to believe in reality (whatever that is) - something about which I know very little (perhaps less and less), but is there in details to discover (in what William Blake called ‘minute particulars’). For much of my life I have been aware that I live ‘after Auschwitz,’ but what does the Shoah become in the light of the violence we are witnessing and particularly ‘after Gaza.’ How is it witnessed - or Bucha or Sudan or Congo - in the life of things around us. Faced with icons (poems without words) reading begins with gazing and words are belated (in waiting, in hiding). Reading and gazing occur in different portions of the brain, and as the mind moves in between what it sees and what it still can't say, it changes; as John Cage sometimes found, self-expression can become self-alteration. Realities I may resist begin to flood. They become transformative. Their resistance to my ‘truths’ intensifies. Like koans.”

What themes do you pursue? Is there an underlying message in your work?

“I'm not sure that there is an underlying message. Perhaps there is an underlying insistence, an imperative. Perhaps icons bear witness; as they face you, you witness their witness. Traditionally religious icons witness may witness the silence of God. Perhaps icons of war can bear witness to a silence (a silencing) - realities with or without God.”

How would you describe your work?

“I don’t know. It keeps changing. It keeps improvising and I keep improvising with it. It is always work in progress. I have taken thousands of photographs and I have made thousands of icons with those photographs. Sometimes what I find startles me, and that is a sign that a work is working (or beginning to work). Walter Benjamin says that unlike particulars can become a way of regarding other particulars and replace Platonic forms and Aristotelian generalities.”

Which artists influence you most?

“Claude Lanzmann, Osip Mandelstam, Raul Hilberg, Timothy Synder, Andrei Rublev, Pavel Florensky, Paul Cezanne, Mark Rothko, William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Miles Davis, Shostakovich, John and Alice Coltrane, among others. There are so many.”

“When nothing is there, play something that isn't - or something as if it were nothing - were not - though necessarily it is - or at least is a residue of its own disappearance - a fading resonance proximate to silence - quieting that quiets - then quieter though never quietest - unfinished silencing - approaching the proximities of impossible but never there (like counting eternally toward infinity but always un- limited) though as if even that might also be possible - though not now, not here, not this. Not yet? If there's nothing to play, play nothing - play beautifully - play whatever you can when you can't. And then pause. As in love.”

What is your creative process like?

“Perhaps I can describe it with a poem (there is a Quebecois saying: ‘Je suis á l'article de la mort’). Although I can't play the piano, I like to think of art as improvising on a piano:

Listen - my piano - fingering in the cruelties - rest-notes with my next breath - pleased with all my life. A little crazy maybe - but though possibly a little - my second person - miming - plays solo while ascending - my mind stumbles - on my tongue its stutter gives more time for me to improvise along the lines I balance - the borders between ‘the’ and ‘an’ where here - ‘à l’article de la mort’ - death sentences are very close to love.”

What is an artist’s role in society and how do you see that evolving?

“I don't know. Perhaps to witness Perhaps to follow the Talmudic instruction, that a just person lives in a world where justice exists. Wallace Stevens says that the imagination is like light, it adds nothing but itself. Perhaps one task for an artist is illumination.”