Interview

Terence McGinity

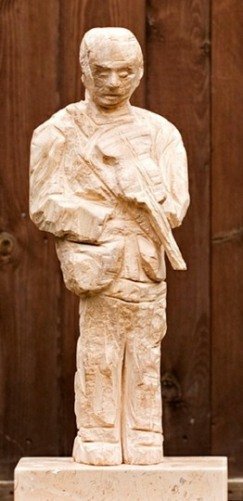

Terence has been carving in stone and wood since 1995, after he returned from New York after a stint on Broadway, as an actor. For the past 28 years, he has been developing his carving skills with the help of excellent teachers in life, drawing and clay sculpting as well as from numerous hours of carving and learning. His work is figurative and that may be because as an actor, he explored the inner and outer of his characters as well as the world they lived in. He has also worked with children and their Special Needs in Education and so a continuous theme running through his work is Attachment and Separation and all that means for the world we live in. Despite the solidity of stone and wood, both mediums lend themselves to expressing fragility. Much of his work touches on vulnerability and in particular, his own as a man.

What is your background and how did you start your journey in the art world?

“My background is twofold. For many years, I worked as an actor, mainly in theatre. I also worked with children with Emotional, behaviour difficulties eventually training in Parent/Child Therapy. In 1995, after a long stint on Broadway, I started Life Classes in Clay at the Working Men’s and Women’s College in Camden Town, London. I soon discovered a love of stone doing a summer course at Tout Quarry, Dorset. For want of a workspace, I trundled my wheelbarrow with Portland Stone and my tools to a remote part of Regents Park and chipped away in all seasons with the London skyline as my view. Then came a 10x8 shed at the bottom of my garden; the only ventilation for the billows of dust being an open door and window and a prayer for a breezy day. I spent 18 years in this ‘cosy’ studio ‘till I managed to finda larger space in Hertfordshire where I have worked for the past 8 years.”

What inspires you?

“I loved acting and was serious about developing my skills. But eventually, I needed more creative control and working with my hands seemed to offer that. And that is mainly what inspires me: to be a ‘man-midwife’ to what emerges from an intricate creative process. I used to feel that the winding woodland path through my garden was like an umbilical cord and my shed the womb. Well, that’s how I felt. Each time a sculpture is finished there is a quiet sense of triumph. Each time someone sees a sculpture and even, perhaps, wants to give it a home there is also a sense of triumph. But by ‘triumph’ I mean satisfaction and joy that someone has appreciated my work. I felt that as an actor too. I have found that the Ego tends to get in the way.”

What themes do you pursue? Is there an underlying message in your work?

“Attachment Theory was very important for my work with children. The themes of Attachment, Separation and Loss all underpin my work. Apart from needing an understanding of my own development it was also crucial in helping children and their parents to ‘earn’ a sense of security and safety with theirs. In terms of the Macrocosm I see this work as essential in preventing more wars and strife and indeed, a crucial aspect of our meeting this critical moment in the World’s development and the survival of Life itself. Unless we address the schisms of the past we are bound to perpetuate them. Somehow, my sculpture craves to impart this message.”

“Each time a sculpture is finished there is a quiet sense of triumph. Each time someone sees a sculpture and even, perhaps, wants to give it a home there is also a sense of triumph.”

How would you describe your work?

“My work is mainly figurative. I am deeply aware of the movement in art to ‘break away from the past’. I think of Miro’s heartfelt slogan, “Down with the Mediterranean”. And I think of abstract sculptors I admire such as Hepworth, Serra, Chillida and David Smith as well as many emerging new sculptors. And yet, I am drawn to figures whether animal or human. Perhaps because of my background work. I endeavor to capture an inner life: a lack or need for connection, a vulnerability and fragility. In this, I feel my work is contemporary in a period of extreme uncertainty and anxiety. It wants to show, in Hamlet’s words, “the very age and body of the time its form and pressure.” This I can best do with figurative work either with stone, wood or concrete.”

Which artists influence you most?

“I keep visiting Rembrandt’s late self-portrait at Kenwood House. Hampstead. It doesn’t just try to extend the boundaries of Form. It mirrors the depths of the artist’s soul; the light, the shade and the shadows. Picasso talked about his need to play. I love that quality. Brancusi has taught me about ‘less is more’- constantly refining his work. Gaudier-Brzeska taught me about Direct carving and the power of imagination. I have been taught by Shona sculptors from Zimbabwe. I have learnt a great deal about finishing and polishing stone to bring out the colour. Gormley has taught me about the power of the figure in our landscape and how a standing figure can be imbued with such mystery.”

What is your creative process like?

“Now, if the piece of stone is uncut rock as most of the Zimbabwean stone I use then I let the carving emerge from the stone. If the stone is already cut like the Blue Kilkenny Limestone I need a plan and design before I start. I prepare through drawing and painting especially with oil as it lends itself to 3D-work. I then sketch with charcoal onto the stone and pick up my chisels. I may use a power tool first to take off surplus to requirement stone. Then work on the figure with whatever chisel meets the stone whether it’s hard or softer. Once the figure feels ready I will start the polish with diamond pads and depending on the stone type I may heat with a blow torch before waxing to bring out the colour. A technique I learnt from Shona sculptors. Then I feel the ideal base to give it a ‘stage’. Alabaster is possibly the most challenging when it comes to technique. It bruises easily and so; extra care needs to be made with the chiselling. The angle of strike needs to be more horizontal; any direct strikes will tend to bruise in my experience. Harder stone like Blue Kilkenny limestone can take more direct strikes from a Point. Alabaster and softer stones like Portland, for instance, are also vulnerable in the weak areas like a neck. I’ve had a few decapitations over the years and I tend to reinforce neck areas with something extra to give support.”

What is an artist’s role in society and how do you see that evolving?

“This is hugely challenging surrounded by a sea of suffering in the world. Where do I place myself as an artist? I cannot turn a blind eye and simply carve something aesthetically pleasing. But I can reflect on the beauty amidst the horror as I did with The Cellist of Sarajevo sitting in the ruins playing his cello. The sculpture needs to touch on universal heart strings; something we all share being compassion. I firmly defend the right of expression. Artistic expression is a humane response to an often-inhumane world. I find it heart-warming when artists use their influence to publicly defend Justice. I believe that the act of Creation is antithetical to destruction and oppression. I am encouraged by the decolonisation of art in galleries and museums. Art may have been a product of its time and I appreciate it as such. But I am grateful for any help in understanding the past and the art it produced. We live now.”

Have you had any noteworthy exhibitions you'd like to share?

“So far, I have needed to mount my own exhibitions which have been hugely appreciated and rewarding. It’s always a massive enterprise and so happen irregularly. I hope for Gallery representation that will reduce much of this hard labour. My recent exhibitions include a Group Exhibition, Burgh House, London (2014); Freedom from Torture Charity Auction (2015); Group Exhibition the Brick Lane Gallery (2020); among others.”

Website: www.terrymcginitysculptor.co.uk

Instagram: @terencemcginitysculpture