Interview

Ezekiel Grimsley

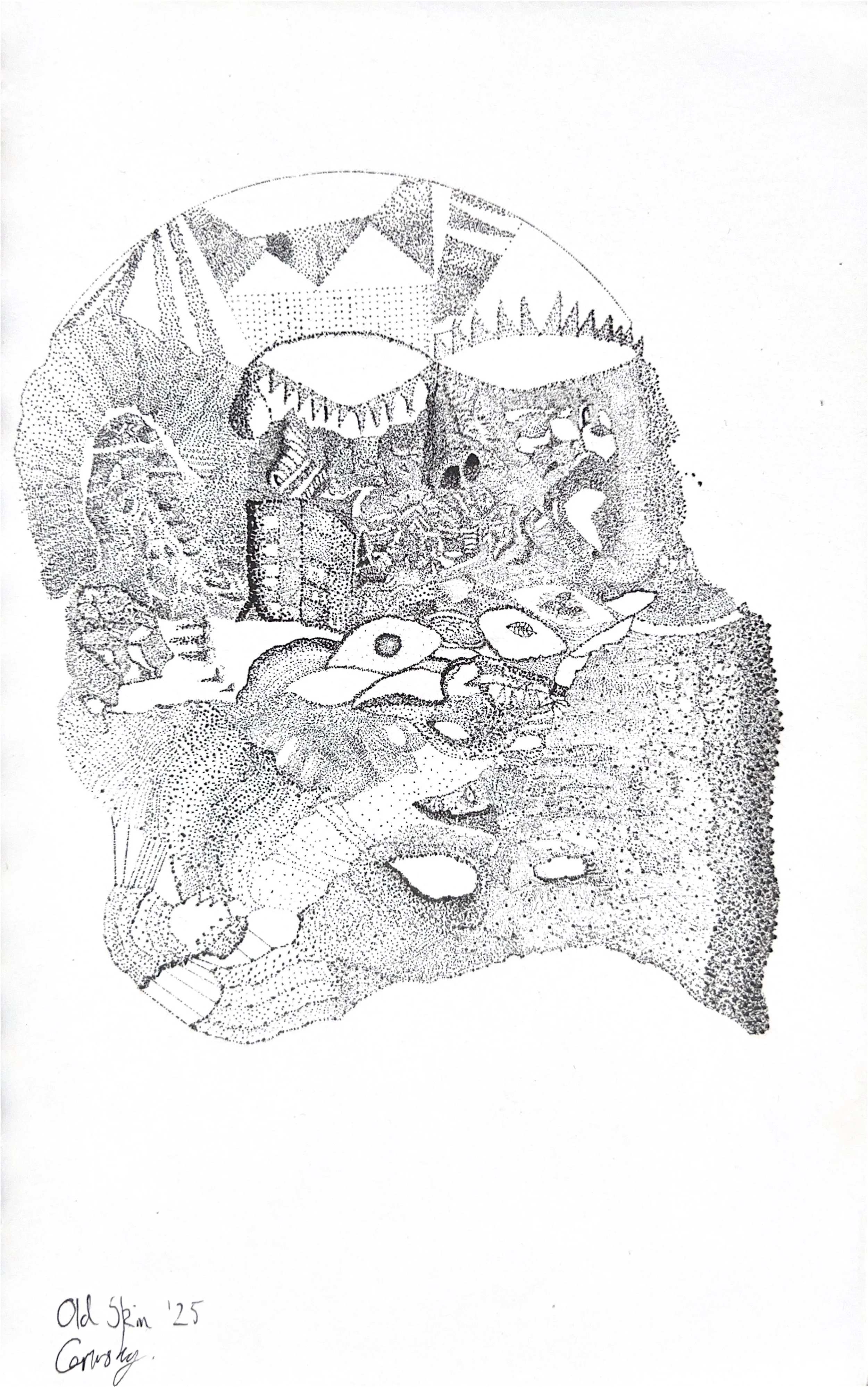

Grinskey is a self-taught artist who works primarily in ink. His work explores the spaces between clarity and uncertainty, often using abstraction to reflect on identity, memory, and transformation. Creating began as a way to slow down and connect with himself, but it has grown into a language of its own. This language continues to teach him patience, honesty, and freedom. Grinskey sees art as both a mirror and a bridge—a place to meet himself and, hopefully, others along the way.

What is your background and how did you start your journey in the art world?

“I work in any medium I can get my hands on, though ink has become my go-to. I’m self-taught, and the process is often slow and unforgiving, but I’ve come to love that. It forces me to focus and slow down, which can be a pretty special place to be. Creating art began as a way to expand my skills, but it quickly became something more—a way to reflect, explore, and connect with myself safely. I used drawing to work on my patchy memory; it became a barrier between me and the world I’m peeking into. The act of creating brought back old memories: being in grade five, completely absorbed in art class before lunch. I was so focused that I missed half of lunch before my teacher finally kicked me out. That feeling of losing track of time and disappearing into the work has always been deeply therapeutic. After that, I didn’t practice much. I was a classical dancer growing up, and that discipline consumed my free time. When I stopped dancing, I thought I had to live a certain kind of life, and I didn’t return to art until my mid-twenties. Since then, I’ve been experimenting with everything—oils, acrylics, pencils, coloured markers, and lately, oil pastels. I’ve always been drawn to monochromatic work, maybe because I’m colour-blind, but lately I’ve started to enjoy exploring colour again. I like filling my life with learning new skills; each one feels like another way to see.”

What does your work aim to say? Does it comment on any current social or political issues?

“It’s difficult to articulate the feeling of not knowing who you are, of peeling away ingrained habits and opening yourself to the possibility that things aren’t as you believed. I often find that abstraction, especially through the stark black-and-white contrast of ink, is the most liberating way to explore that uncertainty. The space between those extremes draws me to build subtle shades, creating depth and complexity through variation. My work aims to bring joy and comfort while reflecting on the challenges of mental health, shaped by my own experiences and those of people close to me.”

Do you plan your work in advance, or is it improvisation?

“It depends. Teaching myself often leads to days of preparation and study, figuring out materials or techniques before I even start. Other times, I just get stuck in, play around with new tools, and try to engage that childlike nature of creating — which can be difficult to reach when you’ve got the responsibilities of adult life. Recently I’ve been exploring how doing less can create more meaningful moments when you do engage. Learning, for me, mostly consists of a friendly level of avoidance, then starting, and then figuring it out. Sometimes, I have a clear idea in mind; other times it’s like a word on the tip of your tongue. It’s not unusual to be experimenting for weeks before it becomes apparent what it’s meant to be. Sometimes it’s not clear until I’m two pieces in. It reveals itself gradually.”

Are there any art world trends are you following?

“I definitely consider myself more of an outsider to the art world. It’s not something I’ve ever been deeply tuned into. I tend to follow my own rhythm and interests rather than what’s trending. I think there’s beauty in making your own lane and sticking to it, staying grounded in what feels real. There’s a lot of noise in the creative space today, but I think that’s beginning to shift. People are slowly moving away from over-consumption and surface-level content, back towards authenticity and connection. This balance between stillness and stimulation is something I think about often, both in life and in art.”

What process, materials and techniques do you use to create your artwork?

“I enjoy exploring a wide range of processes and materials. I like using less typical tools and techniques, finding ways for every element of the process to add another layer of meaning. Lately, I’ve been focused on building more depth and detail, not just within the medium itself, but through how technique and material interact. I treat the entire process as part of the work itself, recognizing that a lot can change between starting a piece and finishing one. While I think routine is important, I also value staying open. I allow the process and whatever’s happening in my life to influence even the smallest details. For example, I recently wrote about struggling to finish a piece titled ‘Old Skin’ on my website. This experience reminded me how much the creative process can mirror personal growth. A holistic approach is important to me, encompassing not just materials, technique, and process, but also philosophy. It’s challenging to want to showcase your best work while also learning to accept when it’s complete.”

“I like to explore a wide range of processes and materials. I enjoy using less typical tools and techniques — finding ways for every element of the process to add another layer of meaning.”

What does your art mean to you?

“My art is essentially an extension of myself. Sometimes it feels overwhelming, while other times it brings an overwhelming clarity and resolve. It’s the most powerful tool in my toolbox. Selfishly, I use it to delve deep within myself, beyond what I could reach in any conversation. It’s funny how something can feel so deeply personal yet, at times, so far detached. I suppose that’s the magic. I don’t think I’ve ever wanted to understand the reasons behind how art has made me feel. I haven’t sought those answers, and I don’t believe they’re necessary to appreciate the outcome. Art represents all of us as humans. Its beauty lies in its ability to be both awful and divine. Art saved my life from a lot of suffering. I would love to live in a world where everyone could set aside even just ten minutes a day to create. I truly believe we would all be far better off.”

What’s your favourite artwork and why?

“The first thing that comes to mind is A Quadrangular Yard by Wu Guanzhong. I remember being in the museum in Hong Kong — all of his work was mind-blowing. I’d never felt such a connection to another artist’s work before. When I visited Hong Kong earlier this year, I was searching for answers. Feeling lost and hoping a trip away would help me reset and get back to creating, I stumbled upon the Wu Guanzhong: Between Black & White exhibition at the HKMOA. It was exactly what I needed – I was completely mesmerised as I walked around. I’ve always felt a strong connection to China ever since I visited as a child. The art, traditions, and culture have stayed with me. Hong Kong felt special, and his takes on the landscapes of mainland China were incredible. They gave me a conviction to embrace the world of ink in a freer way. I was open and searching for answers, and that exhibition definitely delivered.”

Have you had any noteworthy exhibitions you'd like to share?

“I haven’t exhibited much of my work in traditional settings yet. Most of my work has been shared online through my website and personal projects. I’ve always wanted to find meaning before stepping into a gallery space. One of the most meaningful moments for me was publishing Old Skin as part of my Masks series on my website. It felt like an exhibition in itself, an act of honesty. Seeing how people connected with it reminded me of the power of vulnerability when shared through art. I’d love to create exhibitions that blur the line between a gallery and a personal experience. I want people to walk into something living and become part of it, not just looking at work on a wall. That’s what I’m working towards now.”

Website: grinskey.com

Instagram: @grim_zeke