Interview

William Stoehr

When William was 17 years old, he wanted to be an artist, but he didn’t realize his dream immediately. He worked as an engineer and ultimately, president of National Geographic’s mapping business.

After working for forty years, William retired to become a full-time artist. However, it took him a few years to find his voice — the work of his soul. William’s work focuses on victims, witnesses, and survivors of opioid and substance use, and the stigma which inhibits prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.

Exhibited internationally at universities, art centers, museums and galleries, William has participated in more than 100 exhibitions, including 25 solo exhibitions. His work has been recognized several times, including seven best of show awards.

William is a frequent speaker and lecturer, and his work has been featured and reviewed in local, national and international media. On social media, William has more than 300,000 people following his work.

What is your background and how did you start your journey?

“When I was 17, Willem de Kooning was my art hero, but for various reasons, I didn't follow my art. I didn’t paint or draw for 40 years. I was simply in a different life. Then in 2004, I woke up and decided to be an artist. I had a great job at National Geographic, but I decided to resign. I was young enough to begin another career, so I decided to do what I had wanted to do as a teenager.

I began painting while my wife Mary Kay and I lived on the island of St. John, in the US Virgin Islands. My early work was smaller, figurative, and colorful. My technique was slowly getting there, but my purpose was still a question mark. It took a few years for me to recognize my mission — to find my purpose and my voice.”

What inspires you most?

“People have strong, passionate reactions to my work. Some cry and share their heartfelt stories. Some say they intend to get help or take that first step to finally start that intervention. Some thank me simply for recognizing them, making them feel they exist, and that they are not alone.

One time I went to Madrid and witnessed Picasso’s Guernica, arguably the greatest painting of the last hundred years. Everything changed for me. Guernica is more than 25 feet of Cubist chaos. It engulfed me. The smoke filled my lungs. The flames seared my flesh. I could hear them screaming for their lives. I was there. I cried. It was a reality beyond paint and canvas. I am driven to understand how Picasso did it.”

“One woman said that after seeing one of my portraits, she knew I understood her, and that she wanted to die.

The next morning she looked at the very same painting and this time saw hope in the woman’s eyes. She then understood that she too could have hope.

She said, ‘You saved my life.’”

What themes do you pursue? Is there an underlying message in your work?

“My sister died from an opioid overdose. The essence of my art is the exploration of the victims, witnesses, and survivors of opioid use disorder and other addictions. This is a fundamental issue of our time, and my job as an artist is to get you to react, think, ask questions, and respond.

In particular, my exhibitions are intended to normalize the discussion and help eliminate the stigma that keeps people from getting the help they need. Stigma inhibits prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.”

How would you describe your work?

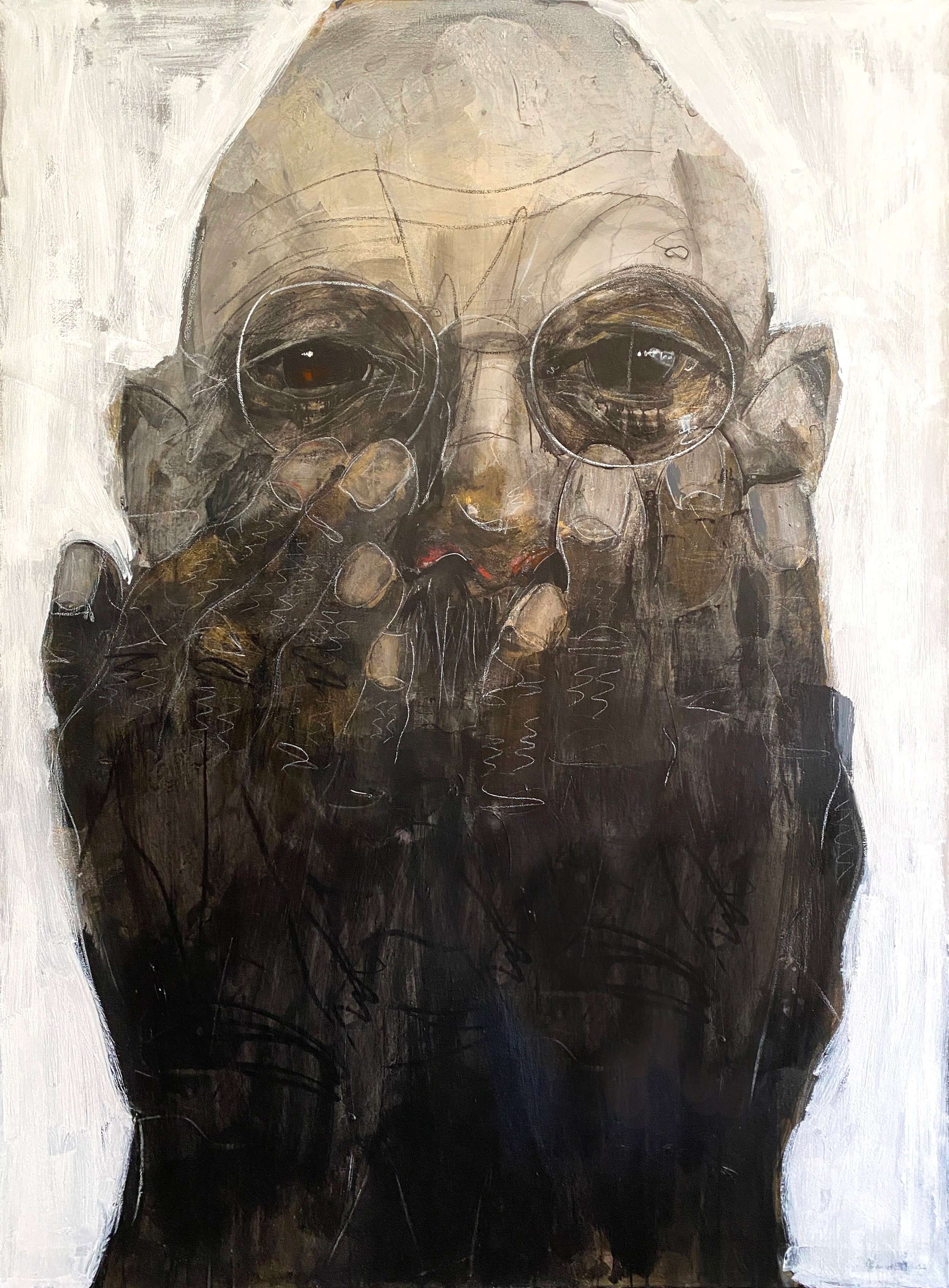

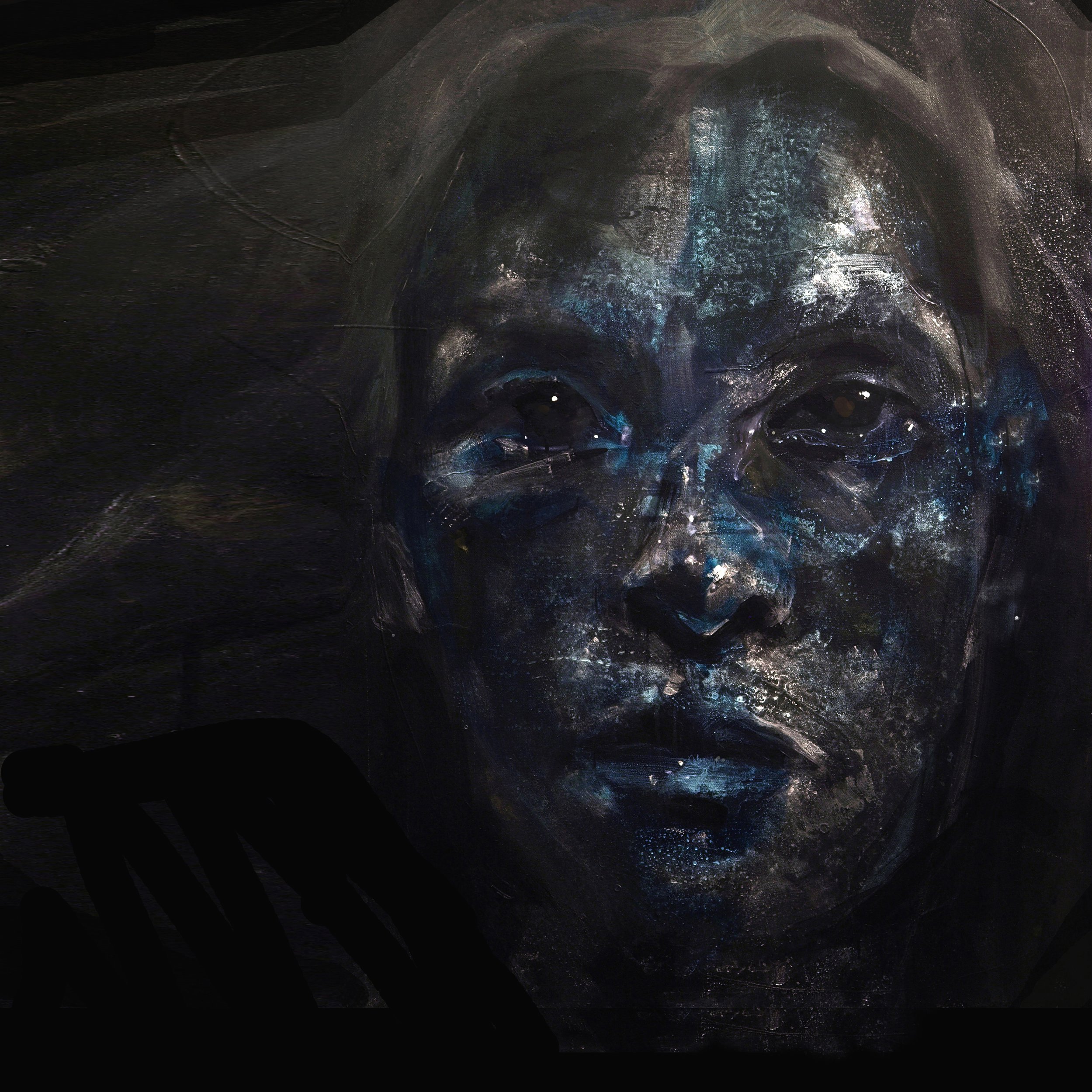

“I always struggle with this, but here goes: I paint large portraits, and many of my paintings are self-portraits. My work is informed by the thinking of the seminal Cubists and by my interest in neuroscience and the visual brain. My style is unmistakable, yet the qualities from one painting to the next appear different but somehow similar. I’ve parlayed problems and experiments into major elements of my style.”

Which artists influence you most?

“I have to mention the abstract expressionists, in particular, de Kooning, Pollock, and Kline. Other major influences include Marlene Dumas and Oswaldo Guayasamin. They have all influenced how I paint, but I am also interested in how Picasso and the Cubists thought about reality, and how we actually interpret images.”

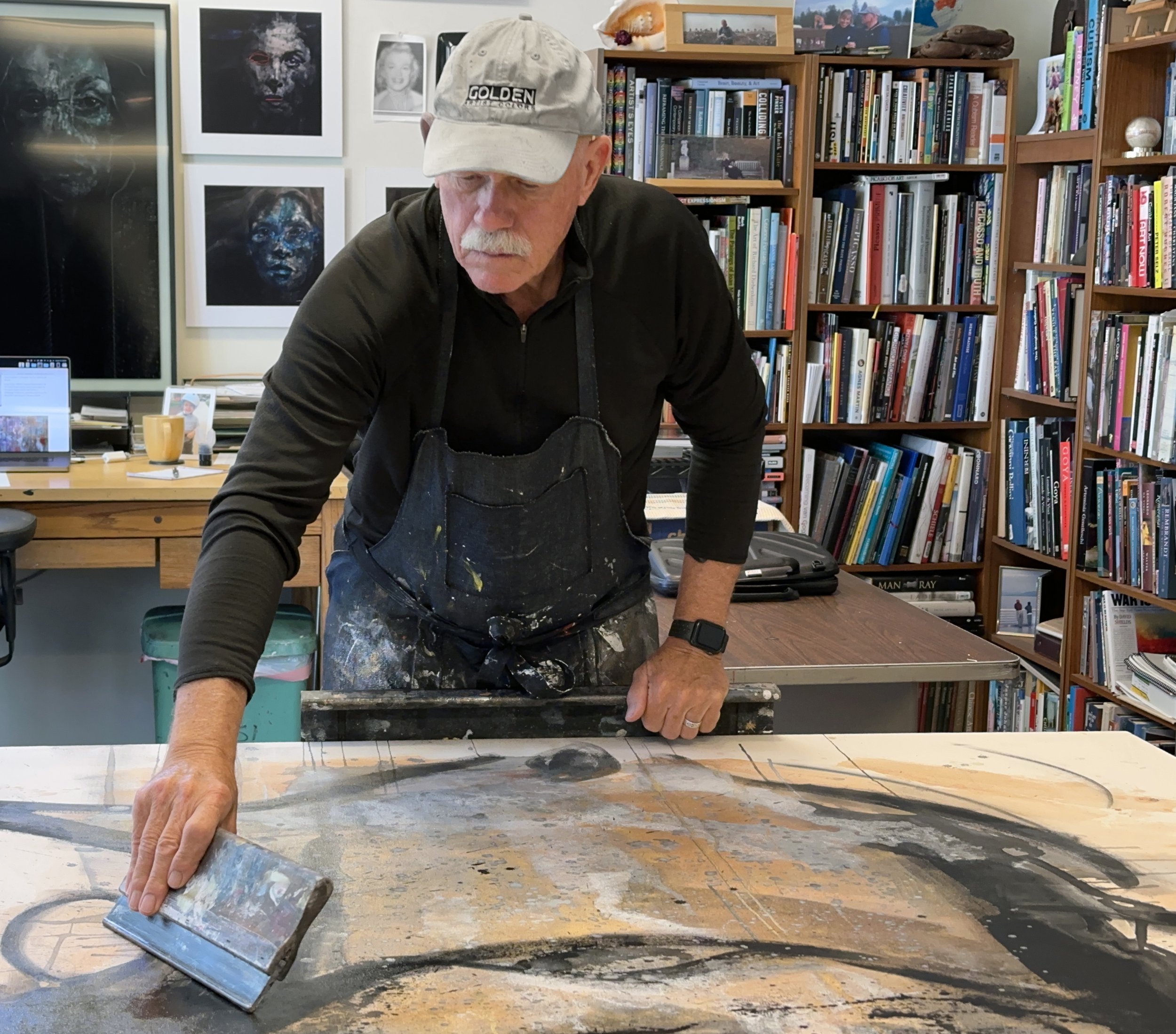

What is your creative process like?

“I don’t do preliminary sketches; I just paint. I simply mark where I want the eyes, nose, and mouth to be located. Then I drip, brush, pour, scrub, and scrape paint while applying a variety of lines, dots, and other adjustments. I often paint multi-views or facial features slightly out of alignment. I frequently paint vaguely different expressions for each side of the face. I use a limited palette of acrylic paint, along with metallic and iridescent colors that produce patterns with changes in lighting and view angle. I present an ambiguous expression, shared gaze and uncertain context, all calculated to provoke you into creating the narrative. These variations and characteristics might make my portraits appear more real. Half-remembered memories and your state of mind affect perception.

I’ve recently started using digital tools. I start with repurposed high-resolution images of my own in-process portraits and original digital drawings. I continue to work on them on my iPad, where I add marks, masks, enhancements, and graphic overlays to the base image, which I then reproduce as an individual image or video.”

What is an artist’s role in society and how do you see that evolving?

“I have a couple of favorite quotes that I keep on my desk. One is by Nina Simone, ‘An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.’ The other is by Robert Hughes, ‘If art can’t tell us about the world we live in, then I don’t believe there is much point in having it.’

A single painting can touch so many people in so many different ways. I believe in the power of art to help break down the stigma of addiction, and I’m motivated to take my art to the next level in this service.

Digital art and platforms have greatly increased my ability to present my message to so many more people around the world.”

Have you had any noteworthy exhibitions you'd like to share?

“My most recent solo exhibit was actually two concurrent and joint exhibitions in the Denver area entitled ‘Stigma and Survival’. There were more than 40 paintings in two locations on either side of the city. One was at the University of Colorado, and the other at the Foothills Art Center. Each program also included panel discussions and presentations related to opioid use disorder. You can see the catalogue here.”